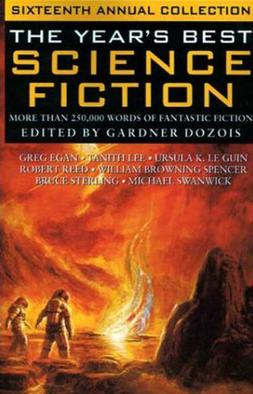

It’s not immediately obvious, but the year in question is 1998. This whopper of a book, containing over a quarter million words of fiction, begins with a 50-page summary of all the science fiction novels, short stories, collections, magazines, movies, TV shows, and more that appeared in 1998. It’s humorous in retrospect that editor Gardner Dozois says South Park is beginning to grow repetitive and he predicts its influence is beginning to wane, since it’s still making new episodes over twenty years later.

The first story in the collection is “Oceanic” by Greg Egan. Despite taking place in the far future on a world where people change their sex from time to time, it’s a realistic examination of religious belief. Our narrator first believes the religion of his parents, gets introduced to another religion, goes to college and learns about problems with his religion, stops being a literal believer but holds on to the essence of the religion, then finally becomes an atheist. A very realistic faith journey.

“Approaching Perimelasma” by Geoffrey A. Landis mainly consists of scientific explanations of how black holes and wormholes work, so it’s a bit dry, but the idea that time turns into space and space into time when you enter a black hole is interestingly described. A cool hard sci fi story.

Many of the stories in this collection deal with immortality. “Jedella Ghost” by Tanith Lee concerns a mysterious woman who doesn’t know about death or aging arriving in town. In “The Island of the Immortals” by Ursula K. Le Guin, immortality isn’t desirable when you have a body that continues to deteriorate. “Divided by Infinity” by Robert Charles Wilson shows us how horrifying immortality is when you end up being the last human left alive. “The Days of Solomon Gursky” by Ian McDonald, on the other hand, presents immortality as desirable, but I don’t buy it. Wouldn’t anyone get bored of living after millions of years?

As you’d expect, many of the stories deal with making first contact with an alien species. In “Craphound” by Cory Doctorow, which I heard narrated on a podcast before, aliens are interested in scouring rummage sales and buying second-hand stuff from us. In “The Very Pulse of the Machine” by Michael Swanwick, a woman drags her friend’s body across the surface of Io after a rover crash. The moon starts talking to her, claiming to be an ancient machine created by aliens, but is she hallucinating?

“Story of Your Life” by Ted Chiang is the most famous story in this collection as it was turned into the movie Arrival in 2016. Compared to Arrival, the short story is more philosophical. Due to how it’s written, the surprise twist isn’t as surprising as it is in the movie. The story makes more sense than the movie because it’s able to take more time explaining, but that also blunts the emotional impact. The movie has higher stakes, of course, but a short story having low stakes makes sense. One of the best stories in this collection. I’m glad I read it.

“The Dancing Floor” by Cherry Wilder doesn’t feel like a stand-alone story. We’re told the main character Taya grew up on an alien planet, but it’s mentioned in passing, so this feels like a sequel or part of a series. There are too many named characters and too much world building to keep track of for a short story. Taya is part of a team investigating an alien artifact called The Dancing Floor. There are several good surprise twists at the end.

There are several stories in this collection I’d classify as “action” stories. A couple spies infiltrate a secret Chinese base containing underground starships in “Taklamakan” by Bruce Sterling. “Sea Change, with Monsters” by Paul J. McAuley features a woman whose job is to kill genetically engineered monsters left over from the last war. She goes to a monastery where the monks have a terrible secret. Great world building in this one. “The Halfway House at the Heart of Darkness” by William Browning Spencer is about a woman addicted to chemically-enhanced virtual reality going to rehab and ending up having to save her therapist.

“Grist” by Tony Daniel concerns a substance called grist which can be used to create whatever you want. It’s a type of programable matter. After people die, their corpses are still animated by the technology living on in their brains. A pointedly non-celibate priest is tasked with trying to prevent an upcoming war. He likes to balance rocks on top of each other up to 20 feet high as a hobby. Some people have heightened awareness due to technology, including being able to predict the future. The story is partly told from the point of view of an enhanced ferret, which I love. Apparently, women still menstruate 1000 years in the future even though birth control methods that eliminate menstruation have been around since before this book was written. Overall, a strange and fun story.

Science fiction is often concerned with discrimination. “Free in Asveroth” by Jim Grimsley tells the tale of beings known as “jumpers” who are colonized by a group of two legs and kept locked up. However, three of them manage to escape. “The Cuckoo’s Boys” by Robert Reed tells us of a genius who creates a virus which makes hundreds of thousands of women all over the world get pregnant with his clones. The gifted clones are targeted by killers all over the world for polluting the gene pool, but for some reason, the killers wait 13 years before beginning their reign of terror. In “Voivodoi” by Liz Williams, the narrator’s brother has a medical condition she keeps secret from the reader until the end, although you can probably guess what it is from the title.

Some of the stories take place after Earth has become inhabitable. In “This Side of Independence” by Rob Chilson, Geelie is tasked with evicting the last people still living on a frozen earth, but they don’t want to leave. Before the general public became aware of global warming, many science fiction stories featured a frozen Earth. The Earth is also frozen in “Saddlepoint: Roughneck” by Stephen Baxter.

In Baxter’s story, aliens come to earth in the 21st century, and give Frank and Xenia a chance to take an interstellar voyage that lasts one year from their point of view, but when they return, centuries have passed for everyone else. They’re relics from the past, which makes them superior to future humans. In this time, Japanese live on the moon. Frank, a rich, capitalist American relic with a move-fast-break-things approach, saves the moon by doing unethical things. As Frank would say, you’ve got to break a few eggs to make an omelet. I’m not sure if the story condones or condemns his behavior. Xenia, our viewpoint character, doesn’t entirely approve, but Frank gets what he wants in the end at the expense of others. It seems short-sighted to present Japanese living centuries in the future still behaving in a stereotypical 20th century way, though.

Instead of being frozen, Earth is destroyed by an asteroid in “Down in the Dark” by William Barton. Only a couple thousand humans remain on various planets in the solar system. Without resupplies from earth, it’s only a matter of time before they die out. The narrator is a guy who’s no longer interested in sex despite women trying to seduce him by getting naked in front of him. (There was a similar scene in “Grist”. Was this a theme at the time?) He’s on Titan where a strange phenomenon might just be signs of life. It’s largely melancholy throughout, but has a hopeful ending.

The only stories in this collection I didn’t care for are “Unborn Again” by Chris Lawson and “La Cenerentola” by Gwyneth Jones. In Lawson’s story, a woman with Parkinson’s uses illegal stem cells to cure her disease, but the procedure gives her random pain because instead of stem cells, the Chinese actually gave her brains from infant girls tortured to death due to their one child policy. It’s a moralizing story about how China and stem cells are evil. John Stuart Mill appears in her dreams in order to condemn utilitarianism too.

In Jones’s story, a rich couple from America, the narrator and her wife, travel to Europe where they lust over teenage twins. Something sexual seems to be going on with the twins’ tween sister as well. It’s a creepy story, but it’s also confusing. The moral of the story seems to be that advances in reproductive technology are leading to magic.

“Us” by Howard Waldrop is an alternative history story giving us different versions of how the Lindbergh baby might have turned out. In a different timeline, he could have been the first man on the moon, a minor celebrity, or a humble fisherman.

Dozois saved the best for last. My favorite story in the collection is “The Summer Isles” by Ian R. MacLeod. It’s an alternate history story in which Britain loses World War I and becomes fascist as a result. Jews, homosexuals, and other minority groups are persecuted. The narrator is an Oxford don who is secretly homosexual. He plans to assassinate the dictator while reminiscing about his past. The story is a meditation on history with a melancholy tone. Can one person really change the course of history or are certain events inevitable? Top notch writing. This would make for a great movie.